Researchers have determined that our genome — of modern humans — is formed by fragments of at least four different species. Three of those species — Homo Sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans are known to researchers. However, a new study has proven there is a mysterious fourth kind of species which we know nothing about.

A new study of the genomes of Australasia has revealed sections of DNA that do not match those of any known species of hominid on the planet. The finding shows that the family tree of humans is much more complex than previously thought.

A team of researchers at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE) have published in Nature Genetics the discovery of a new ancestor, hitherto unknown, of modern man.

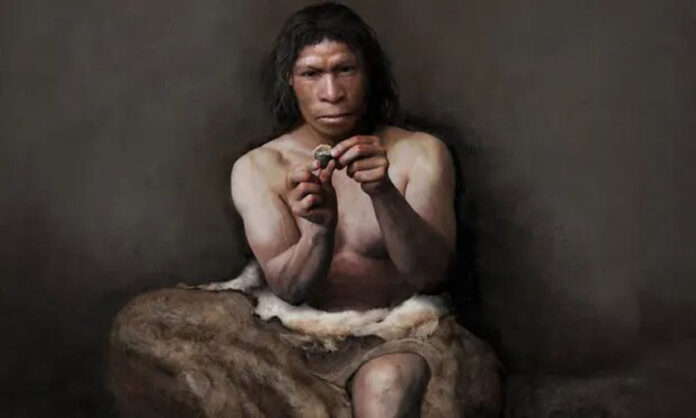

This is a hominid who lived in Southeast Asia and, like Neanderthals and Denisovans, crossed with our direct ancestor’s tens of thousands of years ago.

Although they have not yet found fossils of the new species, the study authors, Mayukh Mondal and Ferran Casals, highlight the importance of genetic studies to reconstruct the origins of our species.

The discovery took place during genetic analysis of a group of individuals of the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean, an isolated population of pygmies that has for more than a century raised numerous paleoanthropological questions.

According to the report:

“We also show that populations from South and Southeast Asia harbor a small proportion of ancestry from an unknown extinct hominid, and this ancestry is absent from Europeans and East Asians”

Applying the most modern analytical techniques, the researchers ran into several fragments of DNA that do not have any correspondence in modern humans who left Africa about 80,000 years ago and ended up populating the rest of the world.

By comparing these foreign gene sequences with the DNA of Neanderthals and Denisovans, whose heritage we have in our genome, scientists could see that there was not a match with any of them.

Therefore, researchers at IBE concluded that the DNA must have belonged to an unknown hominid who shared a common ancestor with the other two species.

It’s the ultimate proof demonstrating that the actual DNA of humans still contains pieces that come from other different ancestors and that we have no clue about our true origins.

According to Jaume Bertranpetit, principal investigator of IBE, “we have found fragments of DNA from an extinct hominid that are part of the genome of modern humans. Shortly we hope to get the full genome from fossil remains.”

For a long time now, numerous investigations have determined that the genome — of modern humans — is formed by fragments of at least four different species. Three of those species – Homo Sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans have been identified by researchers.

Now, researchers have found evidence of the existence of a mysterious fourth kind of species which we know nothing about since researchers have still not found any fossil remains of them.

Could this species be the missing link in the history of mankind?

What we know so far is that there is no doubt that the puzzle of our origins is increasingly complicated.

In order to solve one of the greatest enigmas about the human species, much research will still need to be done.

sourced: